So many writers have been gardeners and have written about gardens that it is likely to be easier to make a listing of those that didn’t. However even on this crowded company, Emily Dickinson stands out. She not solely attended the fragile beauty of circulationers with an artist’s eye—earlier than she’d written any of her well-known verse—however she did so with the eager eye of a botanist, a area of labor then open to anyone with the leisure, curiosity, and creativity to beneathtake it.

“In an period when the scientific establishment barred and bolted its gates to ladies,” Mind Chooseings’ Maria Popova writes, “botany allowed Victorian ladies to enter science via the permissible againdoor of artwork.”

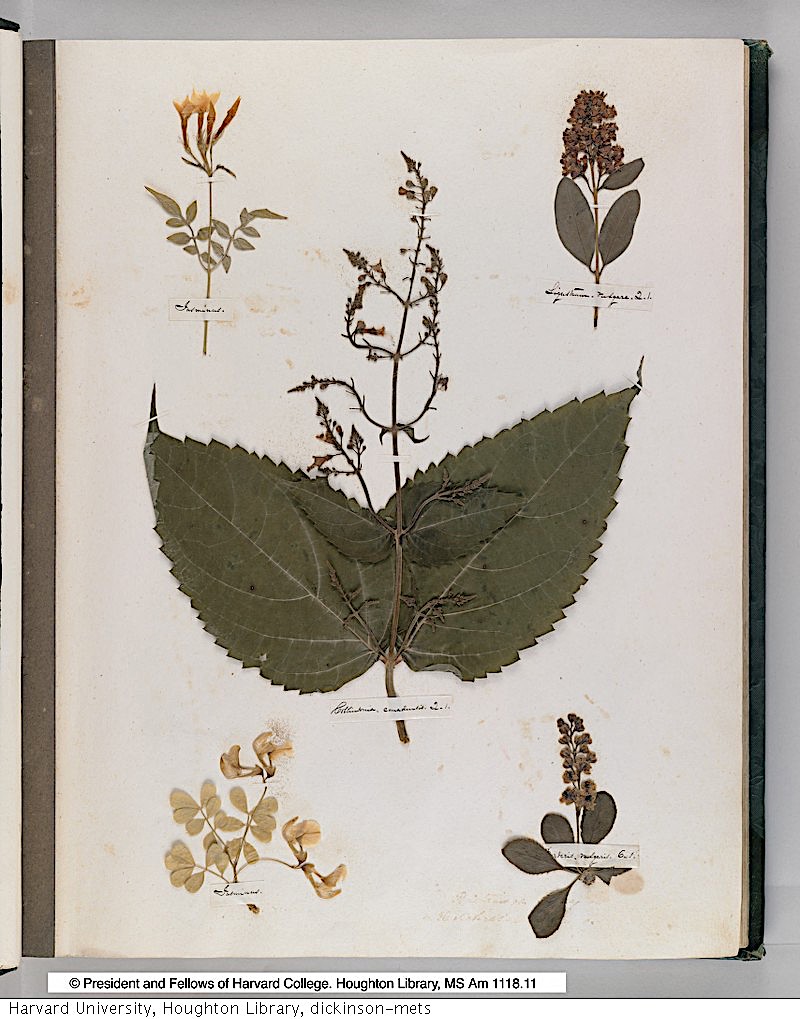

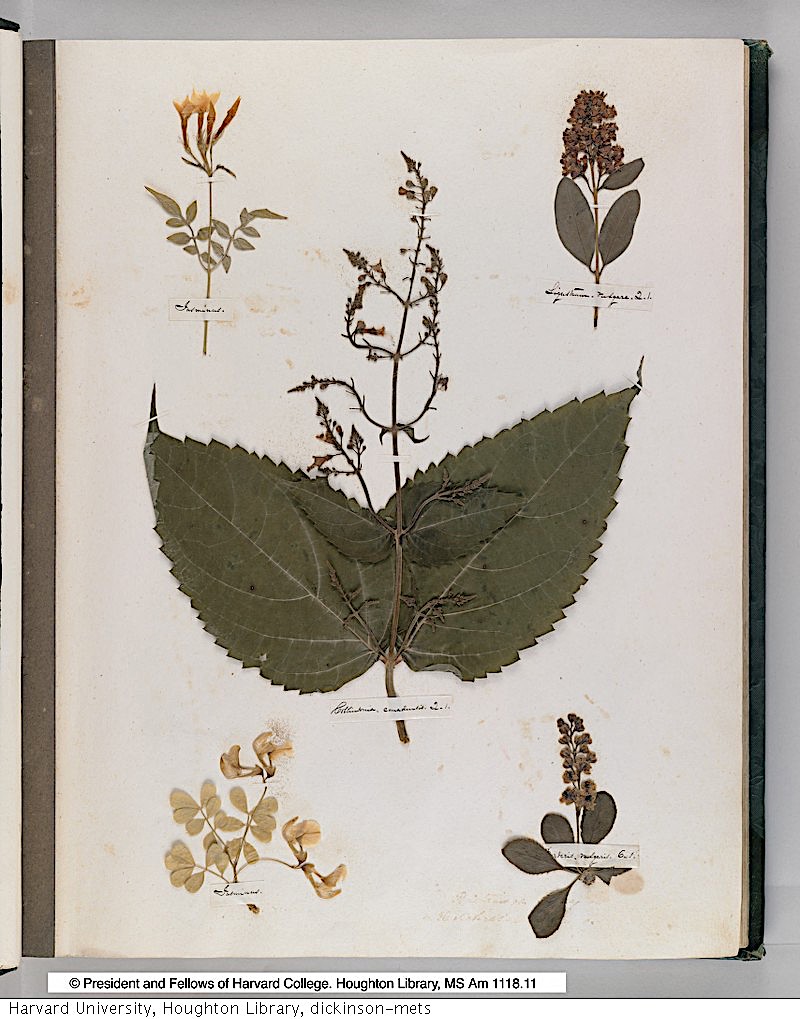

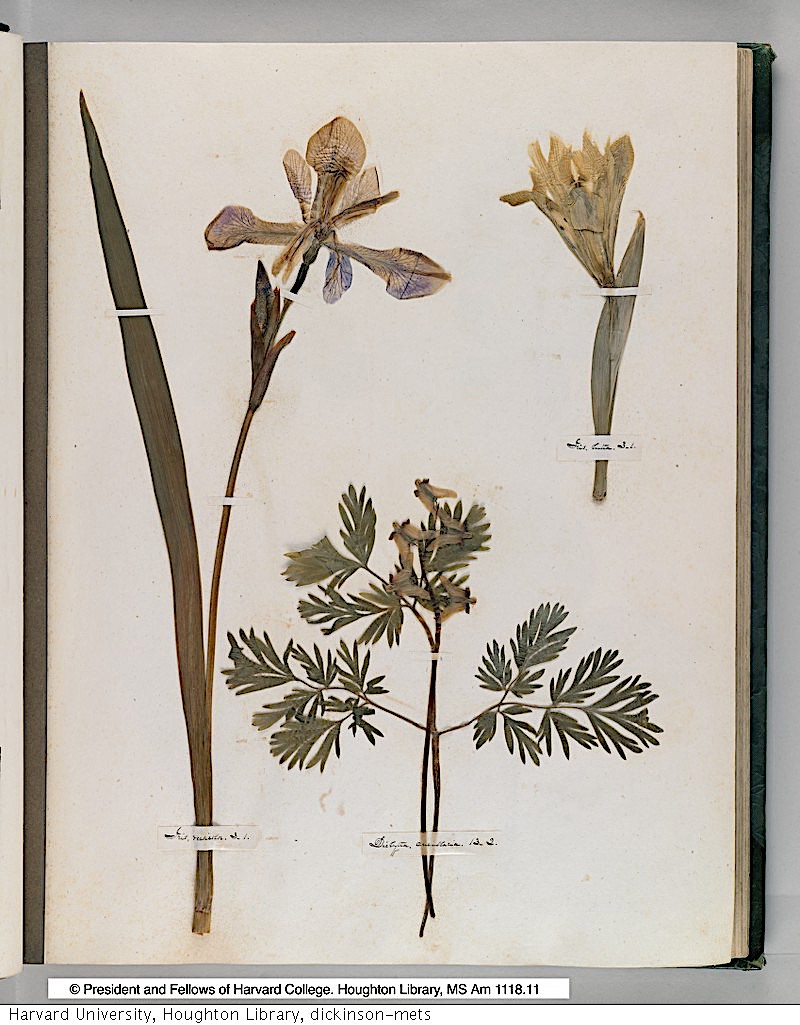

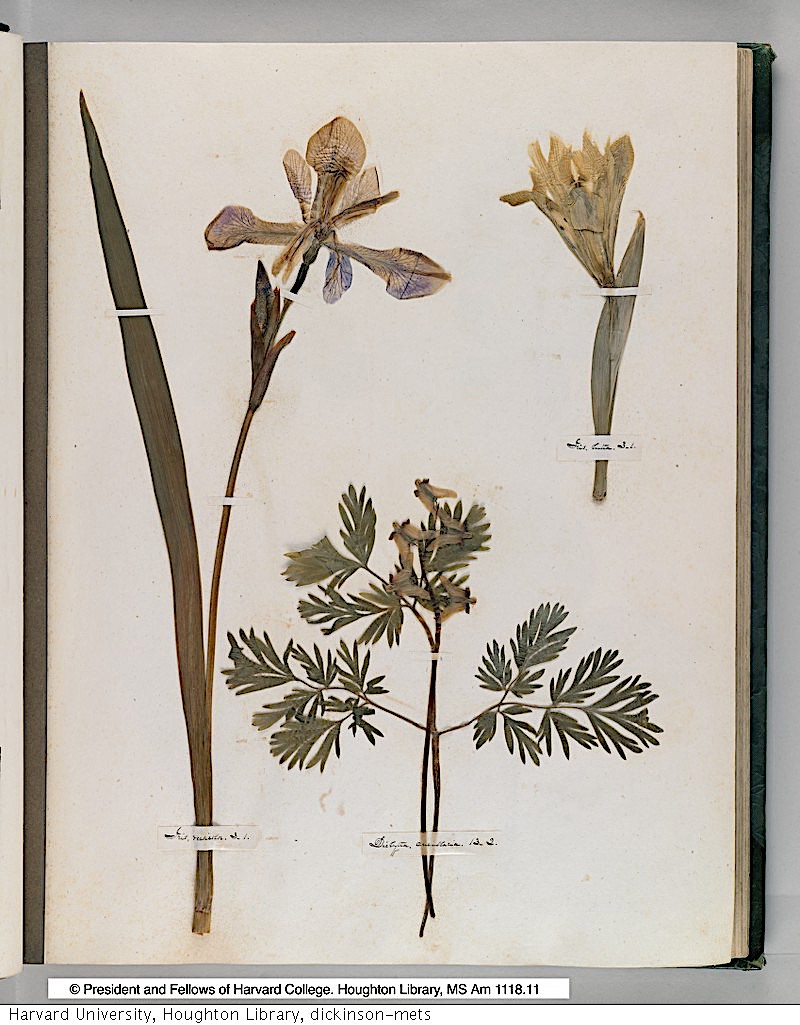

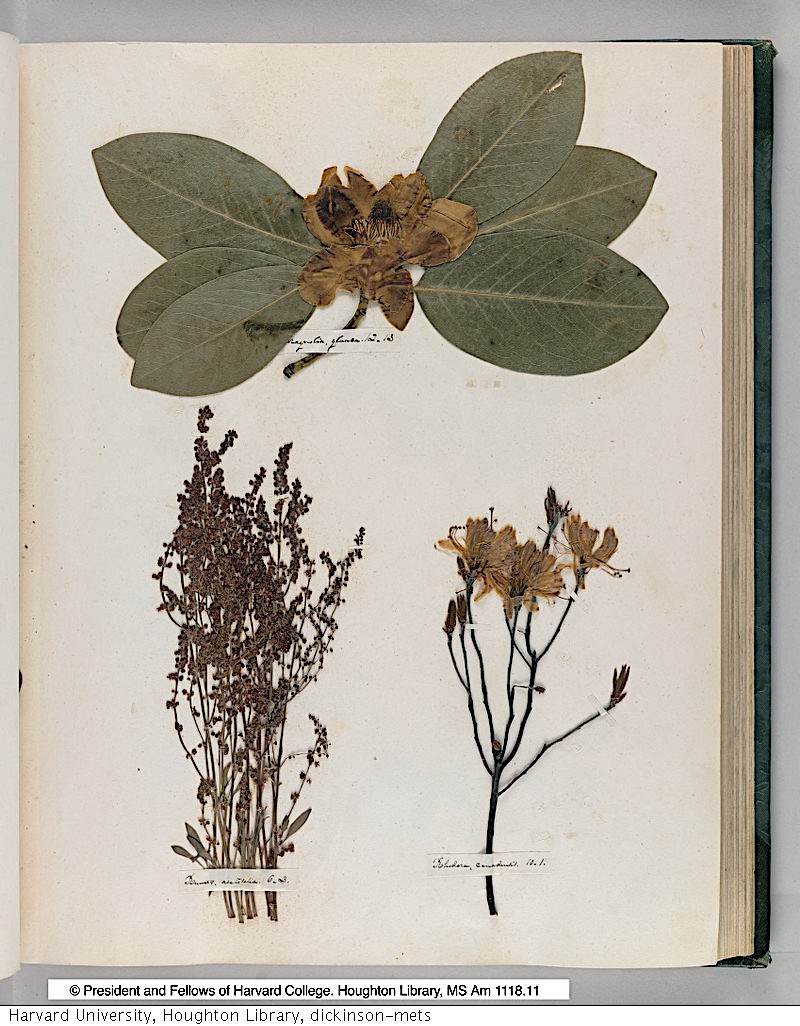

In Dickinson’s case, this concerned the pressing of crops and circulationers in an herbarium, preserving their beauty, and in some meapositive, their color for over 150 years. The Harvard Gazette describes this very fragile guide, made availin a position in 2006 in a full-color digital facsimile on the Harvard Library website:

Assembled in a patterned inexperienced album purchased from the Springarea stationer G. & C. Merriam, the herbarium contains 424 specimens organized on 66 leaves and delicately hooked up with small strips of paper. The specimens are both native crops, crops naturalized to Western Massachusetts, the place Dickinson lived, or homecrops. Each web page is accompanied by a transcription of Dickinson’s neat handwritten labels, which identifies every plant by its scientific identify.

The guide is assumed to have been finished by the point she was 14 years outdated. Lengthy a part of Harvard’s Houghton Library collection, it has additionally lengthy been deal withed as too fragile for anyone to view. The one entry has come within the type of grainy, black and white photographs. For the previous few years, however, scholars and lovers of Dickinson’s work have been capable of see the herbarium in these stunning reproductions.

The pages are so formally composed they appear to be paintings from a distance. Although mostly unknown as a poet in her life, Dickinson was natively famend in Amherst as a gardener and “professional plant identifier,” notes Sara C. Ditsworth. The herbarium might or might not supply a window of perception into Dickinson’s literary thoughts. Houghton Library curator Leslie A. Morris, who wrote the forward to the facsimile edition, appears skeptical. “I believe that you would learn loads into the herbarium in order for youed to,” she says, “however you don’t have any manner of knowing.”

And but we do. It might be impossible to sepafee Dickinson the gardener and botanist from Dickinson the poet and author. As Ditsworth factors out, “according to Judith Farr, writer of The Gardens of Emily Dickinson, one-third of Dickinson’s poems and half of her letters malestion circulationers. She refers to crops virtually 600 occasions,” including 350 references to circulationers. Each her herbarium and her poetry may be situated withwithin the nineteenth century “language of circulationers,” a sentimalestal style that Dickinson made her personal, together with her elliptical entwining of passion and secrecy.

The primary two specimens in Dickinson’s herbarium are the jasmine and the privet: “You’ve got jasmine for poetry and passion” within the language of circulationers, Morris factors out, “and privet,” a hedge plant, “for privacy.” There isn’t any must see this preparement as a prediction of the longer term from the teenage botanist Dickinson. Did she plan from adolescence to turn into a recluse poet in later life? Perhaps not. However we will certainly “learn into” the language of her herbarium among the similar nice themes that recur time and again in her work, automotiveried throughout by pictures of crops and circulationers. See Dickinson’s complete herbarium at Harvard Library’s digital collections right here, or purchase a (very expensive) facsimile edition of the guide right here.

Be aware: Be aware: An earlier version of this submit appeared on our website in 2019.

Related Content:

How Emily Dickinson Writes A Poem: A Quick Video Introduction

The Second Identified Photo of Emily Dickinson Emerges

Josh Jones is a author and musician based mostly in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness